My early-stage academic research made its debut this summer at conferences held by Exeter University and Boston College.

Woo and the Nature of Man is a personal project I’m working on while studying on the Psychedelics Postgraduate Certificate course at the University of Exeter. It looks at the price of men’s mental ill health on society, the high numbers of men dropping out of talk therapy programs, and why many men are seemingly turning to psychedelics for improved health and wellbeing instead. Its goal is to ‘study the potential of emerging health and performance strategies, plus their autonomous application’ – find reliable new ways to sort ourselves out.

This summer I lined up with other swots in the research poster presentations at Integrating Integration, a two-day lecture series held by the University of Exeter. The presentation asked ‘what can services learn from men seeking psychedelic treatment?’ Keynote speaker, ayahuasca anthropologist Evigny Fotiou was notably intrigued by the section on decolonising masculinity. See more in the all-new Research section here.

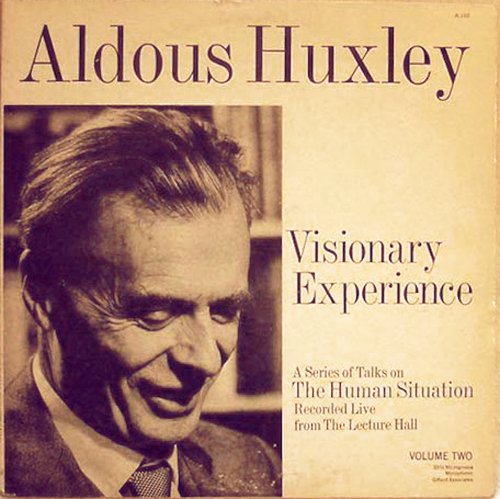

Weeks later I spoke about ‘how psychedelics help men engage with spirituality’ at US university Boston College’s London campus, as part of its Psychology and the Other meet. The whole (rather swanky) conference wasn’t recorded: a baller move in this day and age, but admittedly jarring for someone like myself who’s used to organising events purely for the one photo of Kate Moss arriving that will hopefully appear in The Evening Standard next day.

I ripped off the title Woo and the Nature of Man from the first workplace motivation guide for managers, Work and the Nature of Man written 1967 by Frederick Herzberg. The research is at its conceptual stage (ahem) which means I’m deep-diving for themes in the relevant academic literature that add to or inform the data I’ve picked up personally in what I now refer to as ‘male spaces’.

One finding of note so far is that emerging spiritualities encourage men to explore other forms of unconventional masculinity besides the feminised option offered by contemporary culture – NFL quarterback Aaron Rodgers expressing unconditional cosmic love for his team mates, for example, in contrast to Harry Styles wearing a dress on a magazine cover. Another discovery is that women in what were once men’s roles, like the military, emergency services or professional leadership positions, drop out of trauma services in the same numbers that men do – possibly because our comfort-based culture cannot accommodate the complex experiences that come with a richer and more challenging life path.

I’m studying on the world’s first ever legit university postgrad in psychedelic science and humanities. Sign up for Messages from the Ether below, or follow me on Twitter and Instagram to stay with the vibe.

More from University of Exeter:

Can psychedelic philosophy explain the healing powers of the cosmic whole?